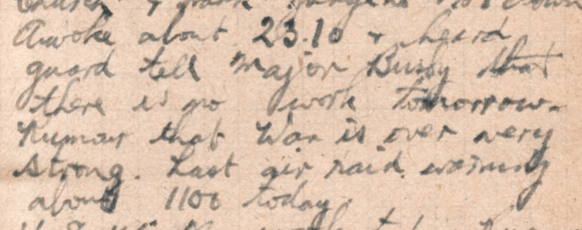

On the 15th of August 1945 my grandad wrote: ‘Awoke about 23.10 & heard guard tell Major Busby that there is no work tomorrow. Rumour that war is over very strong.’ Grandad was a British POW in Hiroshima Camp #6-B at this time. This is his story.

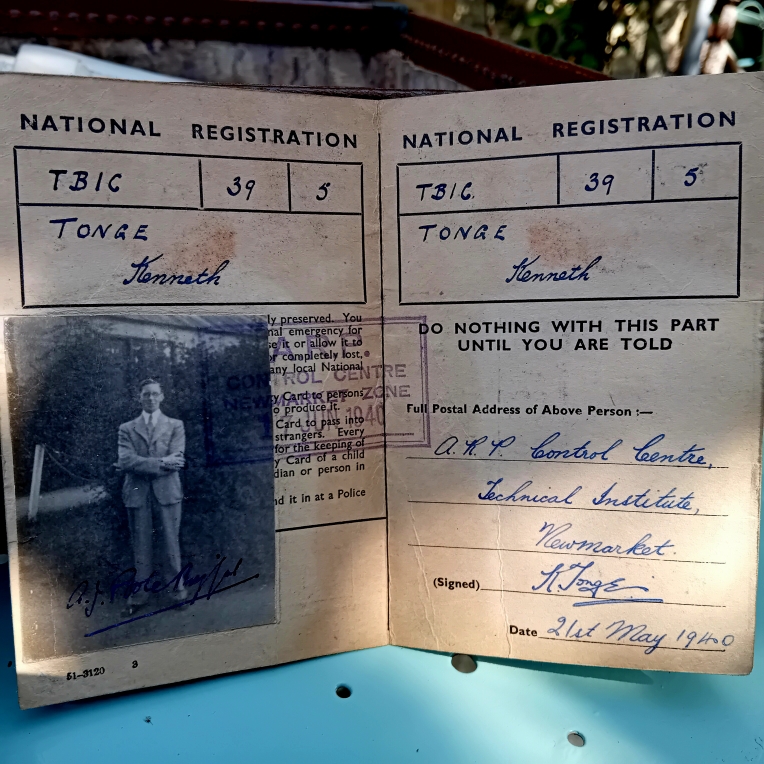

My grandad, Kenneth Tonge, had worked in an Oldham cotton mill since leaving school, but he aspired to be a journalist. In 1939 he got a job as a clerk with the ARP and then in March 1940, aged 20, he registered for military service. Ken saw this as his chance to see more of the world.

He joined the 48th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, RA, and spent the next few months doing aircraft defence work in Essex. His father had served with the Royal Garrison Artillery in the last war. At home on leave, in May 1940, Ken listed some of his ambitions for the years ahead.

In December 1941 the 48th LAA sailed out of the Clyde headed for the Far East. In February 1942 they arrived at Tangjong Priok, the port of Batavia, Java. The island capitulated the next month.

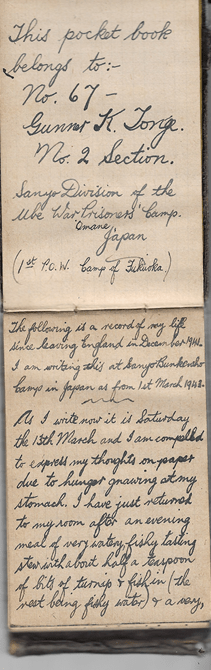

After long route marches, and being detained in prison camps in Batavia for some months, they left for Sumatra. From there, they sailed to Japan on the “Hell Ship” SS Dai Nichi Maru. Around 800 men were crowded onto this old, dilapidated vessel. With no sanitation, dysentery and diarrhoea were soon rife, and they were sometimes battened down. After nearly two months on board, they finally arrived on the island of Honshu in November 1942. Grandad said he was ‘in a sorry state’ by this time. On arrival in the camp he weighed 57 kilos (he was a man of nearly 6 foot). This photograph was taken in December 1942.

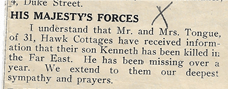

He was officially reported missing in March 1942. It would be over a year until his parents received any news. Then, in April 1943, they were informed that he’d been killed in action. This clipping is from the local parish magazine, kept by my great-grandmother.

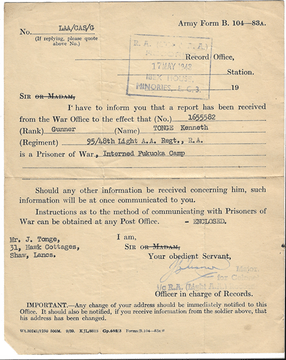

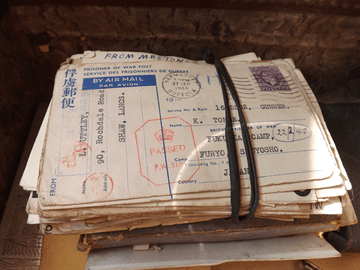

His parents had no body to mourn over, but a memorial service was held for him. My great-grandfather, James, suffered a cerebral haemorrhage after the service and died that day. In May 1943 my great-grandmother, Ellen, was informed that her son had surfaced in a POW camp. He was permitted to send a postcard home.

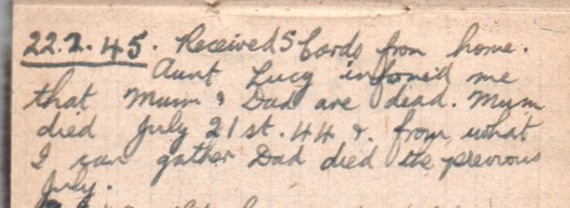

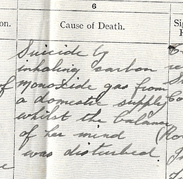

Ken could now write to his mother, but her letters clearly show that her mental health was declining. In July 1944 she committed suicide. She put her head in the gas oven. Letters from England arrived irregularly, and it was February 1945 before Ken had a letter from his aunt informing him that both his parents were dead.

‘This was a great shock to me,’ he wrote, ‘for since leaving England in 1941 I had prayed and looked forward every day to getting home and being with my parents once more.’

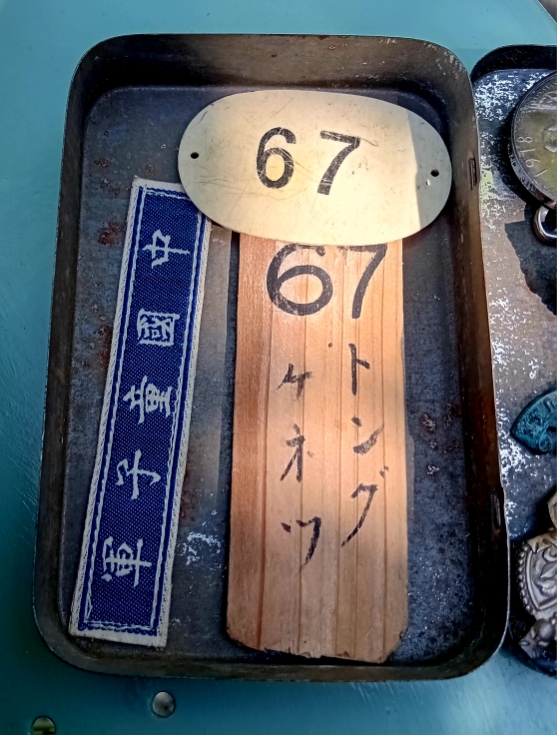

Grandad was a prisoner in ‘Sanyo’ Camp (renamed Hiroshima 6-B in 1945), Omine Machi, near the city of Ube. 472 POW (184 British and 288 American) were imprisoned there at the end of the war. The Americans had arrived in 1944. 31 POW died in the camp.

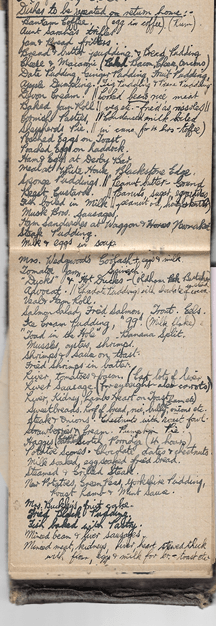

In March 1943 Ken began to keep a secret diary. It documents the day to day reality of being a prisoner, trying to keep alive and the constant hunger (this latter is its main theme). He sustains himself by making lists of the countries he wants to visit one day, books he means to read, and food he intends to enjoy. Meanwhile, if a Japanese woman dropped orange peel at the roadside, the prisoners pounced upon it.

He was prisoner number 67.

Ken was a forced labourer for the Sanyo Muentan Coal Mining Company (‘slave labour’, he called it), working in mines that had been declared unsafe before the war. He was injured twice in tunnel collapses. In addition to malnutrition, at various times he had malaria, beri-beri, dengue fever, dysentery and pneumonia.

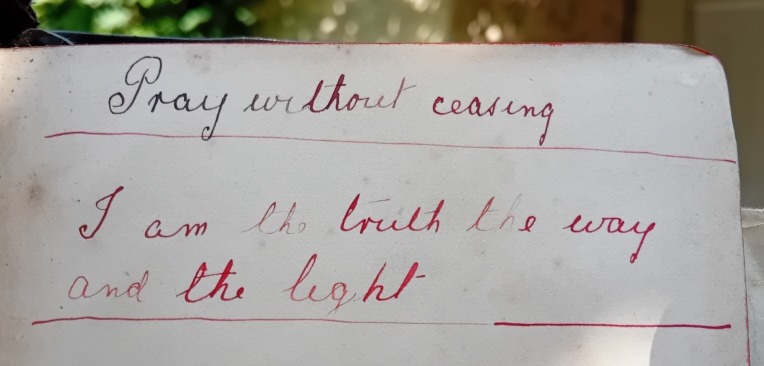

Grandad’s few personal possessions included this bible, which had been given to his father in 1918. This bunch of heather is pressed within its pages. (Is it Lancashire heather? Lucky heather?) The inscription below is in his father’s handwriting.

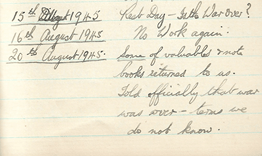

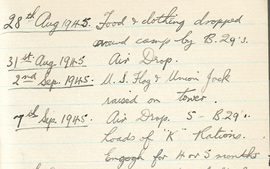

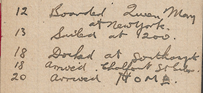

At just after 11pm on the 15th August 1945, rumours began to circulate that the war might be over. On the 16th of August the prisoners weren’t required to work. On the 20th it was officially confirmed that the war had ended.

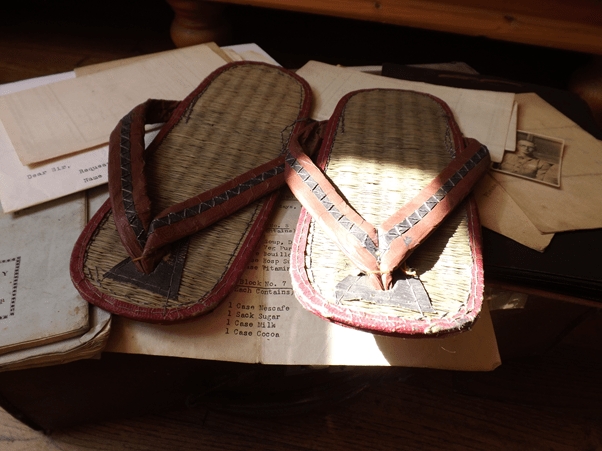

The next days would see airdrops of food. These are the slippers that Ken was wearing in August 1945. (I assume he made them himself.)

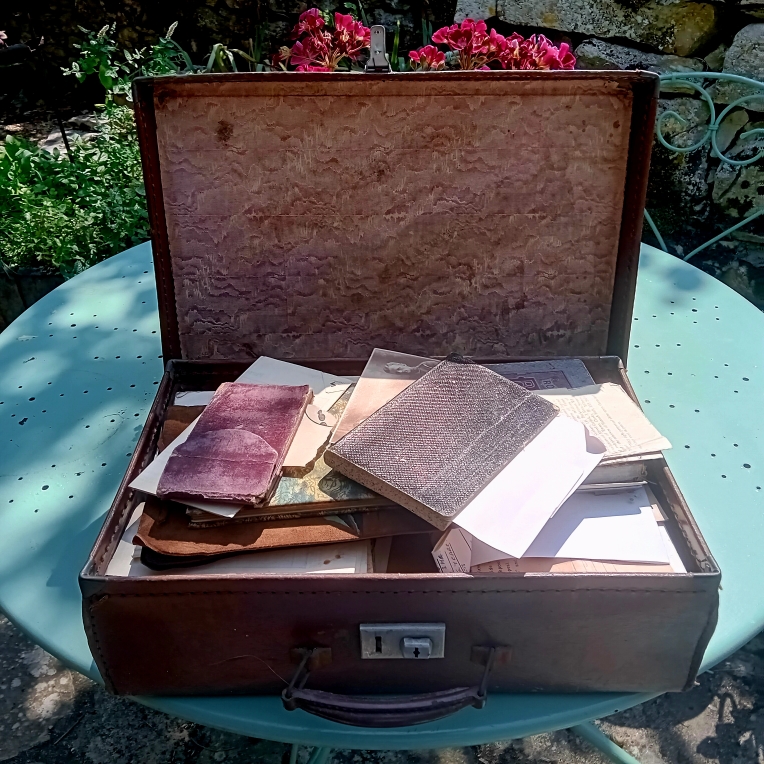

Grandad finally came home on the 20th of November 1945. But his parents’ house was gone and their possessions had already been dispersed. He had nothing but the contents of the small brown suitcase photographed above. (For years afterwards, he’d visit relatives’ houses and say, ‘That used to be my mother’s tablecloth/vase/trifle bowl… etc’)

When Ken came home, he was diagnosed with ‘psychoneurosis’. He suffered terrible nightmares for years afterwards and would have a violent reaction if woken in the night. (My grandmother had a hard time as a young wife.) As a small child, my mum remembered visiting her father in a psychiatric hospital.

There’s a letter in the suitcase, dated 1993, which he wrote to the Far East POW Association, outlining his experiences. ‘I ought to write a book, but that may not get the sheer hideousness of the experience out of the depths of my brain.’ That was five decades after this experience.

My grandad was the strongest, kindest and most gentle man. In the years after the war he studied Esperanto, the international language that was intended to spread peace. He told me Japan was a beautiful country and he hoped he’d be able to return there one day. (Alas, he never had the chance, but I’d love to make that journey for him.)

In June 1946 he wrote:

I have been round the world and have been thrilled and interested in these places I have visited. Three and a half years have been spent in prison camps in Java and Japan, but rather than think three years wasted I would be inclined to say they were a great education.

Today, as I look back, it all seems like a very bad nightmare, but I am grateful for its teachings. I realise the value of being able to write this knowing that whoever reads cannot convict me or kill me for expressing my own thoughts.

The small comforts of life – food, warmth, clothing, love and freedom, are as great as diamonds. After such an experience I cannot fail to be happy… I rejoice in my freedom, the love of my wife and the knowledge that we will have many, many years of happiness coming our way.

Having been declared dead in 1943, he regarded (and treated) every day as a bonus. He got 53 years of bonus days. Grandad passed away in 1996, aged 76. We were very close and I keep this photo of him on my desk.

Grandad always felt that the Far East prisoners of war were forgotten. On his behalf, I thank you for reading this post and remembering these men. #FEPOW. #JVDay80 #WW2